Pallab GhoshScience Correspondent

BBC

BBCListen to Pallab reading this article

Hidden away in a lab in north-west London three black metal robotic hands move eerily on an engineering work bench. No claws, or pincers, but four fingers and a thumb opening and closing slowly, with joints in all the right places.

“We’re not trying to build Terminator,” jokes Rich Walker, director of Shadow Robot, the firm that made them.

Bespectacled, with long hair and a beard and moustache, he seems more like a latter-day hippy than a tech whizz, and he is clearly proud as he shows me around his firm.

“We set out to build the robot that helps you, that makes your life better, your general-purpose servant that can do anything around the home, do all the housework…”

But there’s a deeper ambition: to address one of the UK’s most pressing challenges – the escalating crisis in social care.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesThere were 131,000 vacancies for adult care workers in England, a report by charity, Skills for Care, found last year. And in all, around two million people aged 65 and over in England are living with unmet care needs, according to Age UK.

By 2050, one in four people in the UK expected to be aged 65 or over, potentially putting more strain still on the care system.

Which is where robots come in.

The previous government announced a £34m investment in developing robots that could potentially be used to give care. It went as far as saying, in 2019, that “within the next 20 years, autonomous systems like… robots will become a normal part of our lives, transforming the way we live, work and travel.”

Could this “techno-solutionism” – which sounds more like something out of a sci-fi film – really be the solution? And would you really trust your elderly relatives, or yourself when you’re at your most vulnerable with what is essentially a very strong machine?

Workouts with Pepper the robot

Japan offers a peek into a future with robots living among us.

Ten years ago, its government began offering subsidies to robot manufacturers to develop and popularise the use of robots in care homes – fuelled in part by an ageing population and relative lack of care home staff.

Dr James Wright, an AI specialist and visiting professor at Queen Mary University of London, spent seven months observing them. And specifically, looking at how well they worked in a Japanese care home.

In all, three types of robots were studied: the first, called HUG, was designed by Fuji Corporation in Japan and looked like a highly sophisticated walking frame. It had support pads that people could lean right into, and it helped carers lift people from bed to, say, a wheelchair or the toilet.

NurPhoto via Getty Images

NurPhoto via Getty ImagesThe second, meanwhile, looked a bit like a baby seal and was called Paro. This robot, intended to stimulate dementia patients, was trained to respond to being stroked through movements and sounds.

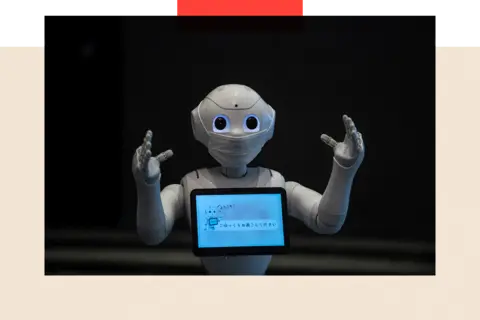

The third was a small friendly-looking humanoid robot called Pepper. It could give instructions and also demonstrate exercises by moving its arms – and was used to lead exercise classes in the care home.

Even before he started observing them, Dr Wright had bought into the hype a little.

“I was expecting that the robots would be easily adopted by care workers who were massively overstretched and extremely busy in their work.

“What I found was, almost the opposite.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHe discovered that, in fact, the biggest drain on the time of care home staff was cleaning and recharging the robots – and above all troubleshooting when they went wrong.

“After several weeks the care workers decided the robots were more trouble than they were worth and used them less and less, because they were too busy to use them,” he tells me.

“HUG had to be moved around all the time to get [it] out of the residents’ way. Paro caused distress to one of the residents who had become overly attached to it. And they couldn’t follow Pepper’s exercise routines because it was too short for people to see – and they couldn’t hear it properly because its voice was too high-pitched.”

The The Washington Post via Getty Images

The The Washington Post via Getty ImagesThe teams behind the robots had their own responses to Dr Wright’s research.

The developers behind HUG says that since then they’ve refined the design to make it more compact and user-friendly. Paro’s creator Takanori Shibata said that Paro has been used for 20 years and pointed to trials that demonstrated “clinical evidence of [the] therapeutic effects”. Pepper is now owned by a different company and its software has been substantially updated.

And yet the study was not without merit.

Mr Walker of Shadow Robot is adamant that the use of robots in care should not be dismissed. For one thing, he argues, the next generation of them will be much more capable.

From labs to the real world

Praminda Caleb-Solly, a professor at the University of Nottingham is determined to make these robots work well in practice. “We are trying to get these robots out of the labs into the real world,” she says.

To do this she has set up a network, Emergence, to help connect robot makers with businesses and individuals who will use them – and to find out from elderly people themselves that they’d want from robots.

The answers vary.

Some people have said they want robots with voice interaction and, understandably, a non-threatening appearance. Others want a “cute design”. But many requests come down to the practical way they’d like the robot to adapt to their changing needs – and for the robot to charge and clean itself.

“We don’t want to look after the robot – we want the robot to look after us,” said one person who was asked the question.

Caremark

CaremarkSome businesses in the UK are testing out robots too.

Home care provider, Caremark has been trialling Geni, a small voice-activated robot, with some people who use their services in Cheltenham.

One man who has early-onset dementia explained he enjoyed asking Genie to play Glenn Miller songs.

Overall, however, reactions have been “like Marmite,” according to director Michael Folkes – with some people living Geni, and others less complimentary.

But Mr Folkes also stresses these devices aren’t about replacing people. “We’re trying to build a future where carers have more time to care.”

Robot hands: learning from evolution

Back in the laboratory of the Shadow Robot Company in London, Rich Walker points out another big challenge: mastering the perfect robotic hand.

“For the robot to be useful, it needs to have the same ability to interact with the world as [a] human does,” he explains. “And for that it needs human-like dexterity.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe robot hand Mr Walker shows me certainly seems nimble. It’s made from metal and plastic, and fitted with 100 sensors, with the dexterity and strength of a human hand. Each finger moves to touch its thumb smoothly, quickly and precisely, finishing with an ‘OK’ to sign off.

It can even do a Rubik’s Cube, one-handed.

Yet it is still a long way from doing the more delicate tasks, like using a pair of scissors or picking up smaller, more fragile objects.

“The way we use a pair of scissors is quite mind-blowing when you think about it,” Mr Walker says.

“If you try and analyse what happens, you’re using your sense of touch in subtle and precise ways and receiving feedback, which makes you adjust the way you cut. How do you tell a robot how to do that?”

Bloomberg via Getty Images

Bloomberg via Getty ImagesMr Walker’s team, together with 35 other engineering firms, are working to design a hand more like ours – it’s part of what’s known as the Robot Dexterity Programme.

It’s one of the projects run by a government agency called the Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA) that sets out to support scientific research that is high risk (because it might well not work) but also high-reward for its potential to transform society.

The project’s leader, Professor Jenny Read, explains they are looking at how animals move as part of this, to better inform the design not only of the hand but to inform a complete rethink of how robots are made. “One of the very striking things about animal bodies is their grace and efficiency, evolution has ensured that, in fact.

“I think gracefulness really is a form of efficiency.”

Replicating human muscles

Guggi Kofod, an engineer turned entrepreneur from Denmark, is trying to develop artificial muscles for robots that can be used instead of motors.

His Denmark-based firm, Pliantics, is at an early stage of development, but have made the key breakthrough of finding a material that seems to do the job and is durable.

He is driven by deeply personal reasons too.

“Several people near me died from dementia very recently,” he explains. “I see from the people who are caring for dementia patients, and it is very challenging.

“So, if we could build systems that help them to not be scared, and that help them live at least a decent level of life… That’s incredibly motivating for me.”

The muscles his firm designs are made from a soft material that extends and contracts, much like real muscles, when an electric current is applied.

Guugi Kofod is working with Shadow Robot, as part of the ARIA project to develop a robotic human-sized hand whose artificial muscles could give it a more precise and delicate grip.

The ultimate aim is for it to detect small pressure changes when it grips an object, and to know when to stop squeezing, just as the skin on fingertips does.

What robots mean for carers

Dr Wright, who observed the robots in Japan, has one final concern. That is, if they catch on, robots could end up making life worse for human carers.

“The only way that economically you can make this work is to pay the care workers less and have much larger care homes, which are standardised to make it easy for robots to operate in,” he argues.

“As a result, there would be more robots taking care of people, with care workers being paid a minimum wage to service the robots, which is the opposite of this vision that robots are going to give time back to care workers to spend quality time with residents, to talk.”

Other experts are more positive. “It’s going to be a huge industry, given the deficit we have in the workforce right now. The demand for carers as our population ages will be huge,” argues Gopal Ramchurn, a professor of artificial intelligence at the University of Southampton.

He is also CEO of Responsible AI, which is involved in trying to ensure that artificial intelligence systems are safe, reliable, and trustworthy.

But he cites Elon Musk’s Optimus humanoid robot, which served drinks and mingled at a Tesla event last year, as a sign that – like it or not – the robots are coming.

“We are trying to anticipate that future, before the big tech companies come in and deploy these things without asking us what we think about them,” he adds.

So now is the time to develop the right regulations to ensure that the robots work for us, he argues, rather than the other way round.

“We need to be ready for that future.”

Additional reporting: Florence Freeman. Top image credit: Jodi Lai/BBC (Picture is illustrative and not representative of any specific robots in the article)

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published – click here to find out how.