PUBLISHED

March 03, 2024

KARACHI:

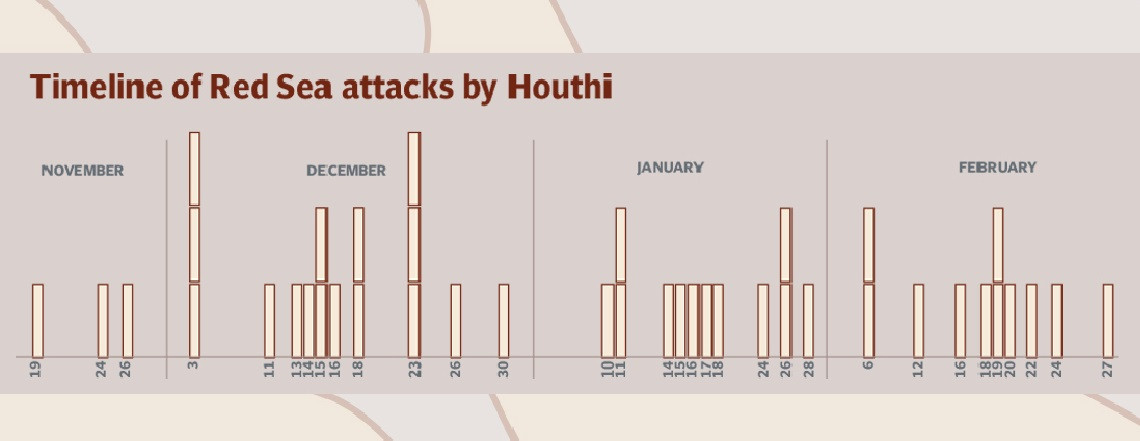

What was feared since Yemen’s Houthis launched the first of their drone attacks against Red Sea shipping has come to pass. A ship attacked by the rebels last month sunk after days of taking on water on Saturday, marking the first commercial vessel to fully destroyed as part their campaign of protest against Israel’s relentless war in Gaza.

The UK-owned, Belize-flagged bulk carrier Rubymar had been drifting northward since it was hit by multiple missiles on February 18 in the Bab el-Mandeb Strait. It was carrying more than 41,000 tonnes of fertiliser, a cargo that could cost anywhere between $12 million to $25 million.

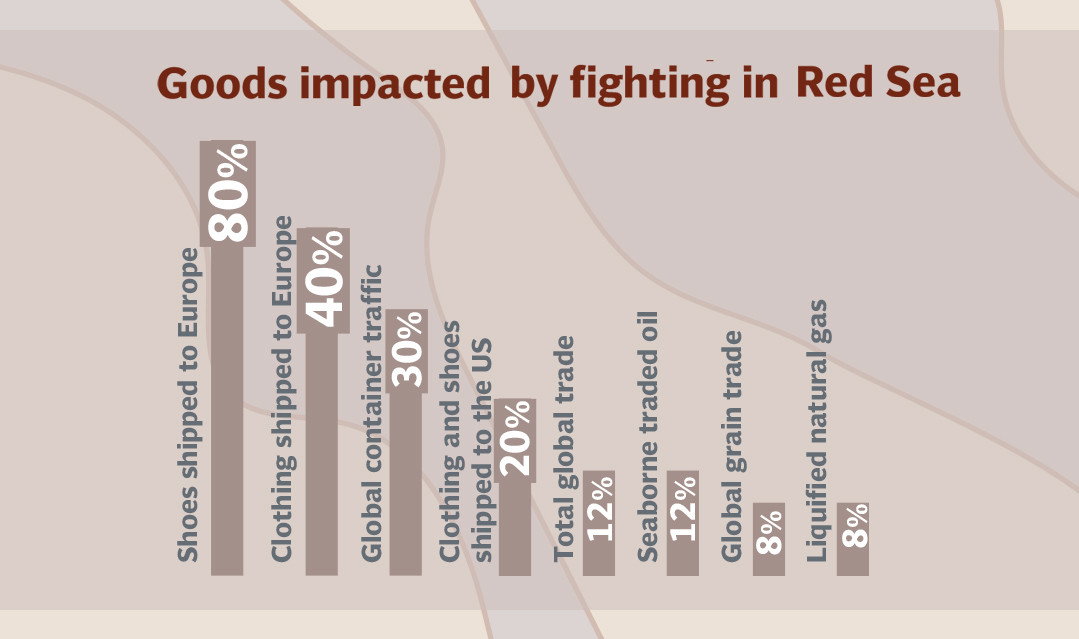

Since the end of last year, Houthi drone and missile attacks against ships in the Red Sea have intensified, disrupting marine traffic through a channel that accounts for around 12% of global maritime transit. Several shipping firms and oil companies have suspended voyages through the shipping lane, rerouting them around the Horn of Africa and incurring costly delays.

The US, in response, has launched a multinational naval operation in the Red Sea along with several air strikes on purported Houthi targets in Yemen. Neither has seemed to have much deterrent effect on the rebels. Meanwhile the cost of countering the group continues to mount unsustainably, as the American military and its allied forces expend munitions worth millions of dollars to take out drones that cost no more than a couple thousand.

To make sense of the surprising effectiveness of low-cost drones in shutting down a crucial node of the global economy, The Express Tribune reached out to drone expert and war historian Dr James Patton Rogers. The Executive Director of the Cornell Brooks Tech Policy Institute and author of ‘Precision: A history of American warfare’, Dr Rogers also advises the UN Security Council, NATO and UK parliament on the global proliferation of high-tech weapons systems.

ET: We discussed, some years back, the revolutionary military use of drones by Azerbaijan against Armenia. Since then, drones have seen heavy use by both Ukraine and Russia against each other, and now by the Houthis against in the Red Sea. How is this different from what we saw in the Azerbaijan-Armenia conflict and the war in Ukraine?

JR: What makes this different is the fact that this is a violent non-state actor group, defined by the UN Security Council as a terrorist organisation, that is able to deploy these long-range precision systems to strike against global supply chains. It’s part of a trend we’ve seen across the region since 2010. From around 60 nations that had military drone programmes back then, there are now 113 – that’s a roughly 88% increase.

And then we have at the very least 65 non-state actor groups that have acquired drone technologies. These range from drug cartels in Mexico, who are targeting law enforcement and local judges and prosecutors, to a range of actors across the Middle East that have access to Iranian-designed systems, which they use to either carry out Tehran’s bidding or for their own political ends.

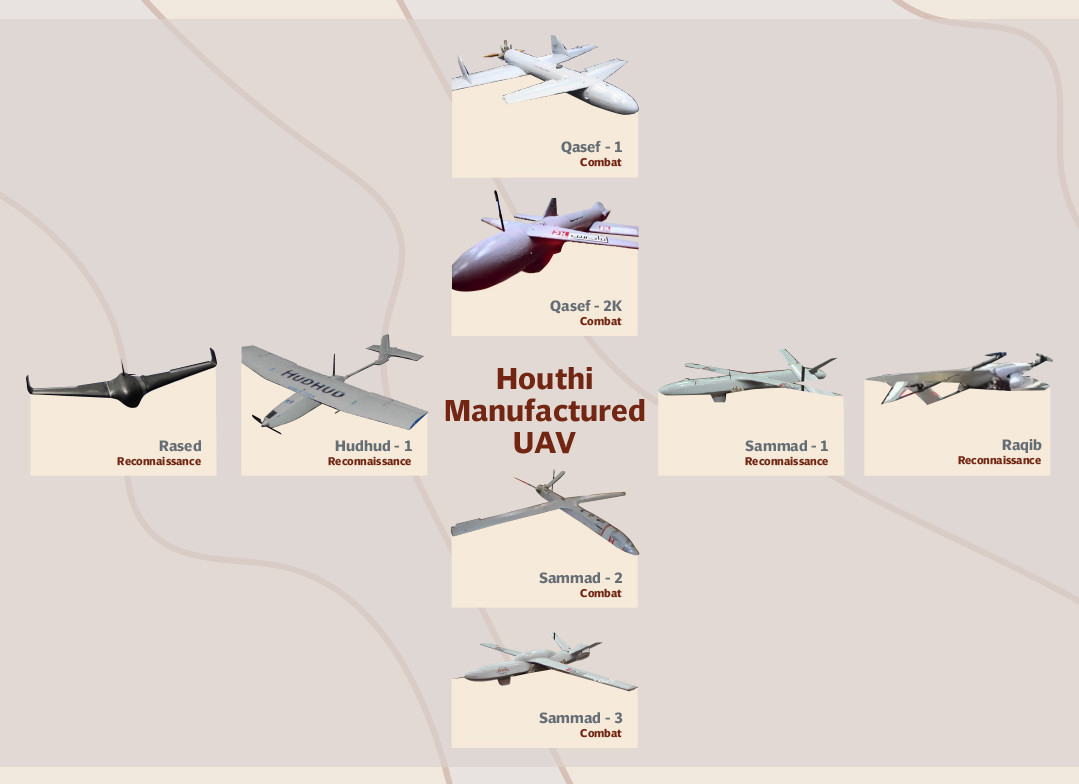

The latter is what we saw with the Houthis, initially at least. When Iran has not wanted to or has been unable to supply these systems to them, the Houthis have been able to lock into the global commercial supply chain of high-tech commercial drone systems and other commercial motors and engines. To show you how easy this is for non-state actors, some of the drone systems I inspected in the Middle East were powered by heavy lawnmower motors.

This is incredibly important for the Houthis because they sit at an incredibly powerful position in the in the global economy. They sit in the south of Yemen, a point at which you have one of the busiest and most important ports in the world. You have shipping passing back and forth in that region. In long-range drones and precision missiles, the Houthis have managed to acquire a weapon that allows them to become the biggest disturbance to the international community.

We shouldn’t be surprised at this. This is something that the Houthis have been leveraging for a while. Back in 2021, three drones targeted the Israeli-badged Mercer Street in a rudimentary drone swarm attack or multi-drone deployment, depending on what you want to call it. They targeted the bridge of this ship, killing the Romanian captain and the British head of security.

We’ve seen this now continue at a pace. It was something I discussed in a 2021 Washington Post article, the fact that it’s these key strategic choke points around the world – these points of global trade and global shipping – that are incredibly vulnerable to the proliferation of drones.

And it’s not just the Houthis. Whether or not these Iranian-designed systems are supplied directly – I think it’s a mix and Iran has and continues to supply some groups with drones – groups like these make and supply each other with drone systems of their own design based on Iranian ones.

Either way, formed as part of what is now being called the Axis of Resistance, they are being mobilised to attack US military, diplomatic and US-allied sites in and around the region. This is culminated in the tragic circumstances on Tower 22, where we had the first deaths of US military personnel by hostile enemy air power in a generation. The last time I could think of that US military personnel were killed by hostile enemy air power was in the Korean War in the early 1950s. And we’ve seen that the attacks are continuing. A US base was struck some days after, killing six Kurdish personnel.

This is the future that I see, where we have the drone in the hands of violent non-state active groups that are able to project their power and try and achieve their political ends through its us. We spent an entire generation post-9/11 trying to reinforce state boundaries and state borders to stop terrorist organisations from committing terrorist attacks in other nation states. But when violent non-state groups have access to long-range drones that can travel 1,500km, perhaps even 2,000km, they can transcend the limitations, regulations and security procedures we’ve put in place since 9/11, and commit terrorist attacks from the safety of their safe havens.

That is a change in the character of terrorism, and it is a change in the character of contemporary conflicts.

ET: Given how quickly drone technology has proliferated among non-state groups, could a comparison be drawn with improvised explosive devices (IEDs) that spread among militant outfits across the world post-9/11?

JR: There are an awful lot of parallels that we can make between the use of the IED and the rise of the drone. In fact, in terms of the history and development of the weapon system, I would say it’s probably from the IED that we can learn the most.

It was often the case that there was a cat and mouse game between the Western allied forces and groups like al Qaeda, the Taliban and those they were fighting in Iraq. The IED started [as a device] buried in the ground, with metal fuses and trigger systems. Once explosive ordnance disposal specialists started to get wise to how to dispose of these quite easily, they were replaced with wooden or plastic elements so that they weren’t so easy to detect. They were also detonated remotely using car key fobs. Once it became harder and harder to successfully detonate IEDs due to the EMP bubble put around Western forces, they started to build them into the walls of compounds or hide them in plastic bags and trees so that they would be above Western forces moving through the region.

Now, it’s at that point that really you can start to see the seeds of the modern drone threat that we have today. It was something that the Islamic State really began to pioneer during their campaign to establish a caliphate in Iraq and Syria, because they saw quite clearly that they were able to lock into this burgeoning commercial high-tech drone supply; something that we hadn’t had before.

Remember, terrorist groups have been trying to use these systems since the 1990s. Aum Shinrikyo, the doomsday terrorist cult in Japan, had experimented with early drones to try and release Sarin liquid over Tokyo. They couldn’t make it work so they ended up filling plastic bags with Sarin liquid, went onto the Tokyo subway, took sharpened umbrellas with them, stabbed the bags, and then of course they killed 14,and injured over a thousand.

The Islamic State was able to smuggle these commercially available quadcopter drones, like the DJI Phantom and Mavic series, through cells in Britain and Europe, and shell companies in Sri Lanka, to basically have a rudimentary air force of their own. They sent these drones up into the air, used them to guide vehicle borne IEDs and suicide bombers to more accurately hit their targets.

When the Islamic State started to see that Western forces were shooting the drones down and gathering any metadata that would help reveal where they were launched from, the group began booby-trapping them with explosives to kill or injure the military forces retrieving them.

Then they started to put mortars and grenades onto these drones and here’s where they essentially became flying IEDs, that either be flown into a target as a kind of early suicide loitering munition, or they would drop a number of munitions onto civilians, aid workers, and advancing forces.

ET: Coming back to the Houthis and the Red Sea, many analysts have pointed out the asymmetry that exists between their drone attacks against shipping and the response by US-led naval forces in the region. While a single successful Houthi drone could deal damage worth hundreds of millions of dollars, there exists no equally low-cost low-tech counter to them. How do you view this asymmetry?

JR: I think it’s exactly the reason why non-state actors are using these systems. It’s that offensive-defensive balance and the cost to counter them that is exactly what they want to try and leverage against the West.

It’s true. There isn’t a quick and easy way of defeating drones. There are a few reasons for that. If you think about the IED problem, it was a ground-based system and we invested billions to try and defeat it. How much was the average price of an IED? Early on probably about five dollars. And some people might say that it’s partly due to that low economic cost that we couldn’t end up fully countering the IED. The cost of human life, meanwhile, meant that those wars went so incredibly disastrously in the end.

But it was our focus on this ground-based threat that meant that we neglected the air-based threats. As I mentioned before, if US and allied forces haven’t faced a hostile enemy air power threat for a generation, then they why would they invest in countering it. That’s not how militaries work. The trouble is that military innovation and military procurement can operate within 30-year cycles. If you don’t keep up to date with these systems, it takes a long time then to be able to develop systems to counter them.

So yeah, of course, we kept up with trying to counter big-ticket items like intercontinental ballistic missiles to make sure that we had air defence in place for deterrent purposes to stop incoming nuclear weapons. But not small drones and these more rudimentary longer range systems, some of which are cast in fiberglass or reinforced with balsa wood, have these commercial elements on board and sometimes deliberately a very low electronic signature, slow speed and low altitude, to evade our current highest levels of radar. Because if you fly low and slow, and have a low electronic signature, that’s how you get through Western air defences. It’s how you get through the air defences of any nation state. It’s exactly how Ukraine has managed to get through Russian air defences and be able to launch attacks on Moscow.

It is all of this – it is the fact that the drone is cheap, it is the fact that the drone can be made on mass and it is the fact that the West has neglected air defence for a generation – that such drones are successful.

ET: Is there right now a system, or the beginnings one, that is able to provide a viable counter to these low-cost low-tech drones?

JR: I am very, very skeptical of any company that says it has the panacea to the problem. We’ve seen over the years now that a lot of companies have said that they have the perfect system to counter drones. In reality, they have an awful lot of problems trying to do this.

Now, there are many reasons for this. Early on, when we had the Islamic State threat, there were companies that had drones that would hunt other drones and have nets deployed to bring drones down. There were companies that had drone guns that could freeze the drone in the sky or make it crash. There were eagles trained to take drones down. This was all well and good when the drone threat was quadcopters deployed one at a time. But then they started to be deployed in the tens, in the 20s. When I was working on the Islamic State threat, we were talking about 83 drones in a 24-hour period, constantly posing a threat above Western forces to the point where force protection officers were telling me that we had lost tactical air superiority.

We have no way of bringing these down and I am very wary of anyone who says that we can fix this problem with one weapon system. There’s been a lot of talk about high intensity lasers and how they can be used to counter these drone systems if they’re mounted on ships or if they’re ground-based. As far as I know, there are very few ships that are mounted with these. I think one US aircraft carrier might have a viable deployable system, but it will take an aircraft carrier to power something like this and to have enough power in reserve to keep this going against a persistent threat.

What we do have that works the most at the moment? Layered defence – it is the reason why you’ve that bases that are under attack are able to defend themselves as much as they can and why ships are able to take out these drones as they fly over the Red Sea. We have the ability to intercept these in the air so you can send up planes that can send missile systems to intercept them. You can send heat-seeking missiles from your own ships or from the ground that can go up and take these drones out.

Or at the very least, in the very last option that you don’t really want to use, we have guns on the ships that have their radar on them. They’re semi automated and as a drone comes in at maybe 500 meters, these are the last line of defense. The reason why I mention them is because most recently we’ve seen those guns have had to be used.

ET: Before the widespread development of cheap drones, Iran often carried out naval exercises using cheap inflatable boats to practice possible attacks against a US aircraft carrier group. The idea, perhaps, was that a swarm of such boats laden with explosives could break through the layered defence that you mention. Do you think beyond the drones it supplied, Iran has influenced the Houthi drone doctrine that we are seeing in the Red Sea?

JR: I think this is something that Iran has been putting forward as its strategy. You have what I call drone deniability from Iran – this ability to supply drones to these allied partner groups around the region, and to supply so many of them that look exactly the same or very similar that you don’t actually know who’s firing them. As attribution becomes difficult, it becomes difficult to hold anyone around directly to account.

This flooding of the region with drones, it’s the same as what you mentioned about these small ships and small boats. You have this overwhelming preponderance of force. This ability to flood the target, to saturate your enemy’s defense, that’s what it’s about. To take out these big-ticket items that we’ve invested in with low-tech smaller items that are deployed en masse.