About three weeks before he was found with 12 slashes between his wrists in a West Virginia hotel room bathtub, journalist Danny Casolaro told his brother that “if an accident happens, it’s not an accident,” according to a new documentary.

Casolaro had spent years entangled in his investigation of an international cabal he called “The Octopus,” a thick web of conspiracies that he told prospective publishers of his book would be “the most explosive investigative story of the 20th Century,” according to the Netflix docuseries “American Conspiracy: The Octopus Murders.”

On Aug. 10, 1991, housekeeping staff at the Sheraton Hotel in Martinsburg, West Virginia, found Casolaro in a bloodied bathtub with his wrists slashed. He told friends and family that he had traveled there to interview a crucial source for his upcoming book.

Tommy Casolaro, the journalist’s brother, received word within a day that 44-year-old Casolaro had died, and that police deemed it a suicide.

Casolaro was facing financial difficulties at the time of his death, writing to his agent that “in September, [he would] be looking into the face of an oncoming train.” Regardless, whether Casolaro took his own life has been hotly debated since his death, according to the Washington Post.

“In my six years as a medic, I’ve never seen anybody ever cut their wrists that many times – the left arm appears to have had eight cuts and the right arm appeared to have had four cuts. It just did not appear that he physically could have done that,” Don Shirley, a firefighter who responded to the scene, told documentarians.

“These were deep cuts… to the point where the tendons had been severed… You cut your tendons, you can’t hold something. Those are simple facts,” Shirley continued.

Casolaro, who covered Watergate in the 1970s and was writing for a tech publication he owned called “Computer Daily” at the time, began the investigation that would consume the rest of his life when he was assigned to research Inslaw.

The tech company that was bankrupted after building a novel software called PROMIS – short for Prosecutor’s Management Information System – for the U.S. Justice Department.

For the first time, the software made case information searchable in a computer database. In 1986, the Justice Department was accused of intentionally driving the software’s parent company into bankruptcy “through trickery, fraud and deceit” by withholding payment, former Attorney General Elliot Richardson said at the time.

HERE’S HOW AI WILL EMPOWER CITIZENS AND ENHANCE LIBERTY

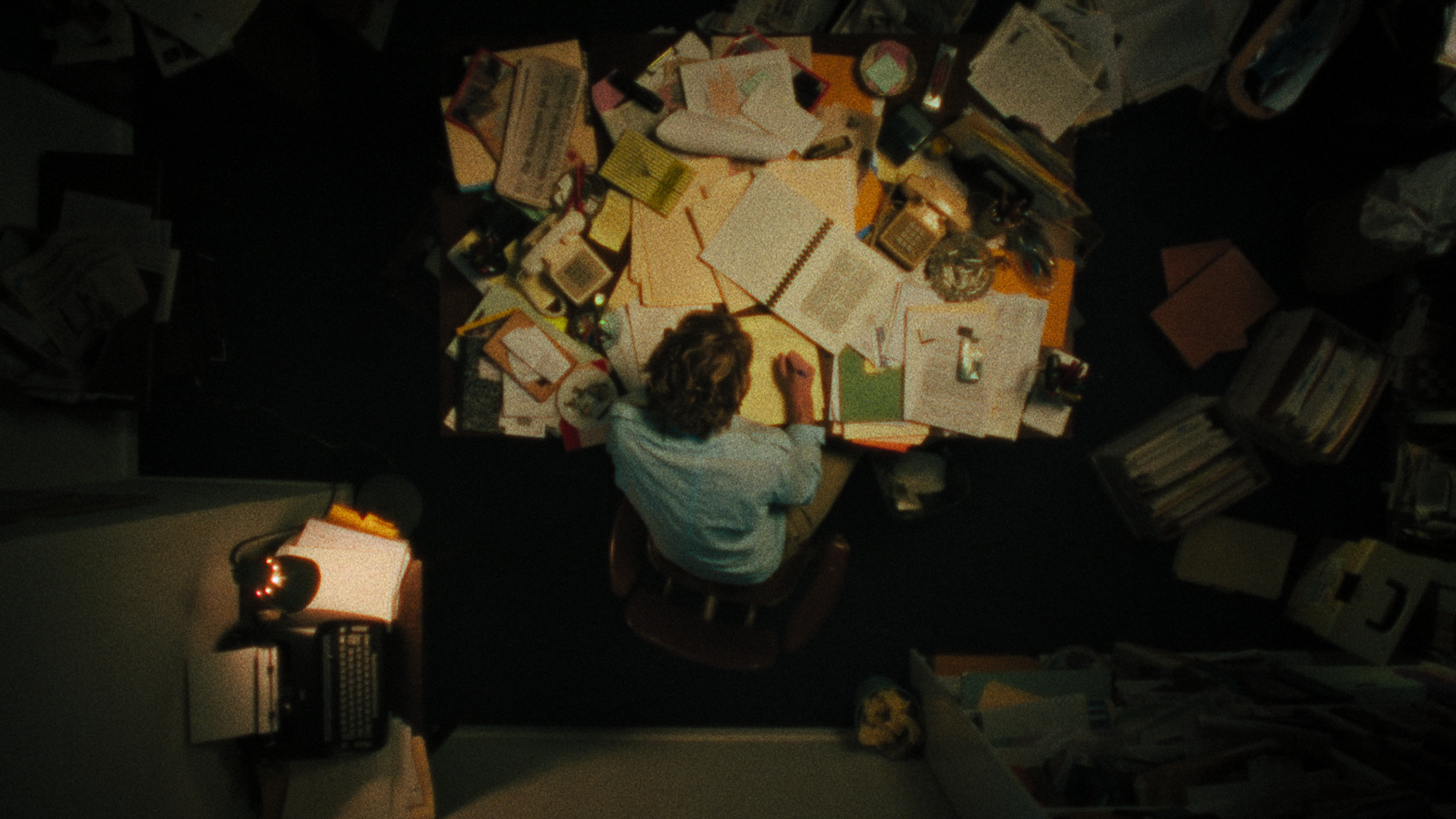

Danny Casolaro, right, was working on a book “about a handful of people who have been able to successfully exploit the secret empires of espionage networks, big oil and organized crime,” he told publishers. He was found dead with slashing wounds to his wrists in a hotel room on Aug. 10, 1991 at 44 years old. (Netflix)

In light of the PROMIS investigation, Richardson said that then-President Reagan’s DOJ was up to something “much dirtier than Watergate.”

Inslaw founder Bill Hamilton, who became a driving source in Casolaro’s research, alleged in court that the DOJ shirked payments for the software to intentionally drive the company under so that Earl Brian, owner of competing computer corporation Hadron and former director of California’s Department of Health Care Services when Reagan was California’s governor, could take control of their assets.

Moreover, Hamilton claimed that Brian had called before the company filed for bankruptcy seeking to purchase Inslaw, saying that he “had a way of making [Hamilton] sell” when he refused.

STREAM MORE, PAY LESS BY LOWERING YOUR MONTHLY STREAMING COSTS

“American Conspiracy: The Octopus Murders” follows Christian Hansen’s attempts to retrace Danny Casolaro’s investigative steps to finish his book – and, he hopes, give more insight into his mysterious death. (Netflix)

Inslaw would later win a case against the Department of Justice for stealing its software in 1998 over claims that the government intentionally stole its software and distributed it illegally – but the case was overturned on appeal.

A theory, one component of Casolaro’s so-called Octopus, is that the Justice Department sold the software abroad to illegally spy on agencies that purchased it.

From there, Casolaro began uncovering prospective theory after prospective theory from interviews with his many furtive contacts.

With Casolaro’s family publicly questioning the suicide designation, citing the growing number of threatening phone calls Casolaro was receiving and the sensitive nature of his work, newscasters and reporters widely speculated about his death. However, as years passed, the case went cold.

‘LOVER, STALKER, KILLER” EXPOSES WOMAN’S ELABORATE PLOT TO ELIMINATE ROMANTIC RIVAL

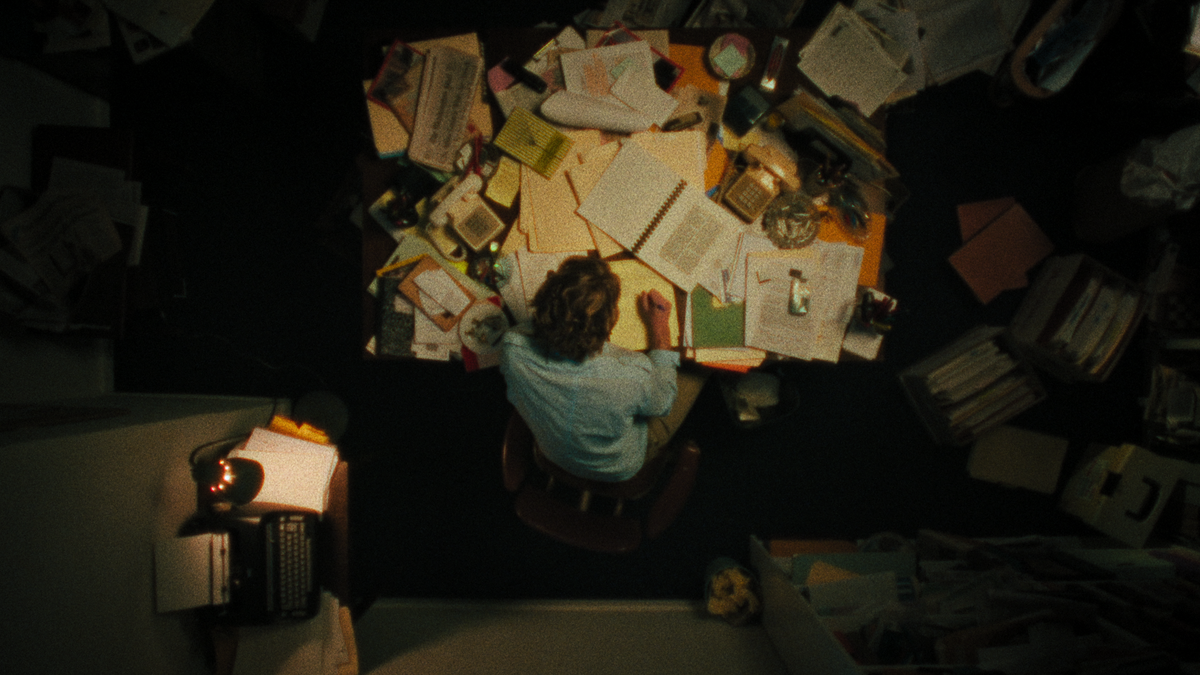

In his 10 years of researching “The Octopus,” Christian Hansen grows closer in resemblance to the man whose research he is trying to unravel. (Netflix)

However, 10 years ago, begetting the Netflix documentary, journalist Christian Hansen grew fascinated with the case and became determined to finish Casolaro’s book in an effort to learn how he died.

Zachary Treitz, Hansen’s childhood friend and the director of the four-part Netflix series, jumped onto the investigation out of concern for his obsessed buddy, but also to figure out if he was onto something.

In his research, showcased by calls to Casolaro’s often-cryptic sources and pages upon pages of laid out documents, Hansen became reminiscent of Casolaro – to make matters stranger, the dead journalist’s longtime friend Ann Klenk remarked that the men even looked alike.

Casolaro’s expansive theory is held up by a bizarre cast of prominent government officials and their affiliates and their links to a criminal underworld. Among them are suspected serial killer and government operative Philip Arthur Thompson, globe-trotting John Philip Nichols, potential spy Robert Booth Nichols and prominently-featured tech wizard Michael Riconosciuto.

Tommy Casolaro told filmmakers that about three weeks before his brother’s death, he told him that “if an accident happens, it’s not an accident.” (Netflix)

The Iran-Contra affair and the 1991 collapse of the Bank of Credit and Commerce International – a financial institution that Casolaro thought made the web of schemes possible – were linked to the wide-spanning conspiracy.

So is a secret government arms factory at the Cabazon Indian reservation in Indio, California. Tribal official Alfred Alvarez and his friends Patricia Castro and Ralph Boger were allegedly killed by Cabazon casino security lead Jimmy Hughes at the behest of Nichols, the tribe’s non-Indian financial consultant, when he asked too many questions about where the casino’s money was going.

Hughes faced felony charges that were later dropped. Nichols was later jailed in the plot, according to the documentary and local news outlets.

Hansen and Treitz vacillate on how much they buy theories bandied by Casolaro’s informants, like Riconosciuto, who the pair interviewed after he was released from a decadeslong prison sentence for 10 criminal counts related to methamphetamine and methadone.

Riconosciuto was jailed just eight days after providing an affidavit for the House Judiciary Committee supporting Inslaw’s claims, saying he worked under the direction of Brian in connection with the software. He said his arrest was retaliatory despite drug charges earlier in his life.

Director Zachary Treitz, left, with Christian Hansen, joins his friend in connecting with Danny Casolaro’s former sources.

Ultimately, the pair uncovered new details about the case never revealed to the public after police in Martinsburg granted Hansen’s public records request from 2013.

Among the paper documents in a box of evidence were statements from another woman in Casolaro’s hotel, claiming that she saw a dark-haired man enter blonde Casolaro’s room on the evening of his death. This detail was not previously included in news coverage, or even in FBI files on the controversial case.

The filmmakers guess, based on circumstances and a composite sketch, that Joseph Cuellar – a former military intelligence official who spoke with Casolaro about his theories in a diner weeks before his death – may have been the second man in the room.

Treitz told the Mirror he was “haunted” since he and Hansen made the connection – in the documentary, Cuellar’s son said that his father specialized in “psychological warfare” and detailed his abilities.

Michael Riconosciuto, a computer expert claiming to have knowledge of covert government operations, is pictured after documentarians pick him up from prison. He was jailed eight days after providing an affidavit regarding Inslaw’s claims that the Justice Department intentionally bankrupted them and stole their software on drug charges he claims are bogus.

Ultimately, Treitz and Hansen told GQ, neither has decided whether Casolaro was murdered or killed himself. In completing the documentary, the pair learned what Casolaro must have – and what may have caused him to take his own life.

CLICK HERE FOR THE FOX NEWS APP

“You have to make a decision for yourself, which I did – are you going to go back to your normal boring life and enjoy small things like movies or barbecues instead of phone calls from the netherworld?” Cheri Seymour, a California-based writer and investigative reporter whose “The Last Circle” is about Casolaro’s reporting and death, told the filmmakers.

“I made a choice between learning the secret of everything, which I realized I would never do, or being happy and having fun,” Hansen said at the end of his 10 years of research and the documentary puzzling and convoluted enough to reflect its own narrative.