Pakistan’s trade could be disrupted if Bangladesh increasingly sources cotton from US to qualify for tariff concessio

ISLAMABAD:

The recently concluded Bangladesh-United States trade agreement underscores a familiar reality of contemporary trade diplomacy: when negotiating with Washington, leverage matters more than aspirations. Like the recent US agreements with India, this deal is markedly asymmetric. The United States has secured substantial commercial and regulatory gains, while Bangladesh has obtained only limited relief on its core export interests.

For Dhaka, the United States is the largest single-country export market, absorbing around $8.7 billion in readymade garments annually, second only to China overall. Bangladesh’s overriding objective was therefore to safeguard its existing market share and sustain the double-digit export growth it has been recording recently.

Against this backdrop, Bangladesh appears to have settled for a marginal reduction in the non-reciprocal tariff from 20% to 19%, the same rate currently applied to Pakistan. It also seems that exporters are taking comfort in Washington’s agreement to permit a specified quota of garments to enter at zero or reduced tariffs, provided they are produced using US-origin cotton and man-made fibre.

By contrast, the United States has secured substantial commercial benefits. Bangladesh has committed to purchasing $15 billion worth of US energy products over the next 15 years, $3.5 billion in US agricultural goods such as cotton, soybean and corn within one year, and 700,000 metric tons of US wheat annually for the next five years.

It also agreed to give preferential access to a broad range of industrial goods such as chemicals, machinery, medical devices, ICT equipment, and buy 14 Boeing aircraft worth approximately $3 billion.

Beyond tariffs and sourcing, Bangladesh has committed to dismantling a wide range of non-tariff barriers. It will accept US standards and recognise certificates issued by US regulatory authorities for health, safety, and other requirements. While this will facilitate US exporters, at the same time it narrows regulatory autonomy of Bangladesh.

The asymmetry is even clearer in digital trade and services. Bangladesh has agreed to remove non-tariff barriers to digital trade, services, and investment, allow free cross-border data transfers, support a permanent WTO moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions, and liberalise its insurance market.

These commitments effectively lock in policy choices that many developing countries prefer to retain, particularly as data governance and digital industrialisation become central to economic sovereignty.

Bangladesh has also undertaken to strengthen intellectual property protections, raise environmental standards, and curb discretionary preferences enjoyed by state-owned enterprises. While such reforms may be defensible in their own right, embedding them as binding trade obligations without meaningful reciprocal market access raises questions of balance and sequencing.

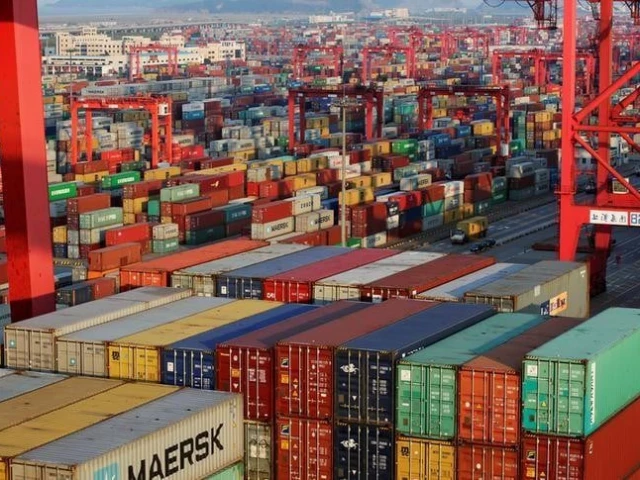

How would this agreement impact Pakistan’s trade? Bangladesh is an important market for Pakistan’s exports of cotton and related products, valued at roughly $700 million. This trade could be disrupted if Bangladesh increasingly sources cotton from the United States to qualify for tariff concessions on garments. Furthermore, Pakistan may face greater competition in its largest single-country export destination from duty-free exports of garments made from the US cotton. These disadvantages would also apply to India.

There is a clear lesson here for developing countries currently negotiating trade agreements with the United States: the Bangladesh model could well become the template. In their pursuit of tariff reductions, they risk locking themselves into binding commitments that steadily erode domestic policy space, particularly by limiting their freedom to source from the most competitive global suppliers.

It is troubling that the world’s richest economy can require one of the poorest to undertake large, guaranteed purchases and accept conditions that Washington itself has been unwilling to commit to at the multilateral level.

This highlights a hard reality of 21st-century trade diplomacy, at least in the US context: rules are shaped less by principles of fairness or development and more by power. Those who have leverage set the terms; those without it are compelled to adjust.

The writer is a member of the National Tariff Policy Board. He has previously served as Pakistan’s ambassador to WTO and FAO’s representative to the United Nations